It is impossible to understand the lynching of Henry Patterson without delving into the years and months leading up to that fateful day on May 11, 1926. LaBelle was a small town with barely 1,000 residents and only a handful of black families that resided in the city during the 1920s. Hendry County, of which LaBelle was the county seat, was largely rural and devoted to cattle ranching and other agricultural pursuits. Like the rest of South Florida in the 1920s, though, LaBelle was in the midst of a land boom that drastically increased the value of land in the region. To account for the expected growth, county leaders issued a bond that would assist in the construction of several roads to be built through the county connecting it to the east and west coast of the state.

This bond issue became the long-term impetus for the lynching. Once passed, residents believed county officials would hire local workers to build the roads. However, road contractors from out of state brought in large numbers of laborers from outside the city for the construction project. Even more problematic from the perspective of locals, hundreds of those workers were Black and were housed at four camps on the outskirts of town. This sudden influx of a large number of African Americans into the nearly all-white town immediately caused problems. From the perspective of white locals, the road workers from out of state took what should have been their jobs and, echoing the views of white southerners regarding the popular view of Black men’s inherent “lust” for white women, the black workers represented threats to white women in town.

It is within this context that we must understand the events that transpired on May 11, 1926. On that date, Henry Patterson, one of the Black men working for the construction companies, approached the home of Hattie Crawford. According to several sources, he did so to ask her for a glass of water. Patterson’s unexpected presence on her back porch startled Crawford, who quickly ran out of her house screaming. Several locals nearby heard her screams and made several deadly assumptions. Rumors spread quickly throughout LaBelle that a Black man assaulted Crawford. Although Crawford would later explain that Patterson did not assault her in any way, her pleas were too, little too late.

Over the next several hours, white mobs gathered and scoured the town in search of Patterson, who fled shortly after Crawford ran from her home. The local sheriff, Dan L. McLaughlin, left town to search for Patterson in Goodno, about seven miles to the east. Later that day, town marshal Radford Edwards and two other men captured Patterson, who was hiding in the underbrush near the Caloosahatchee River. Edwards drove Patterson to the local jail, where they were met by a crowd of around 200 people. Edwards then gave Patterson over to the mob.

"Mob Scene" created by Joel Ralls, Rebeca Parra, and Joshua Oglesby

The mob forced Patterson into a car and paraded through town as part of a motorcade. The mob made its way to Representative James R. Doty’s house, the most senior public official in the county. It was here that several members of the mob allowed Patterson to stumble out of the car and run toward the house. The mob shot him several times. After torturing Patterson for several minutes, the mob put him back on the car, drove down the road, stopped at County Commissioner Melvin Forrey’s store and apartment, and begged him to come down and see what they had done. Forrey hid in his apartment with his family and never appeared. The mob then drove south past the unfinished Hendry County Courthouse and lynched Patterson.

News of the lynching spread quickly and captured the attention of the nation. Although mob members threatened the local editor of the Hendry County News, there was little they could do to stymie word from reaching all corners of the United States. Reports appeared in newspapers in Ft. Myers, New York City, and Los Angeles the next day.

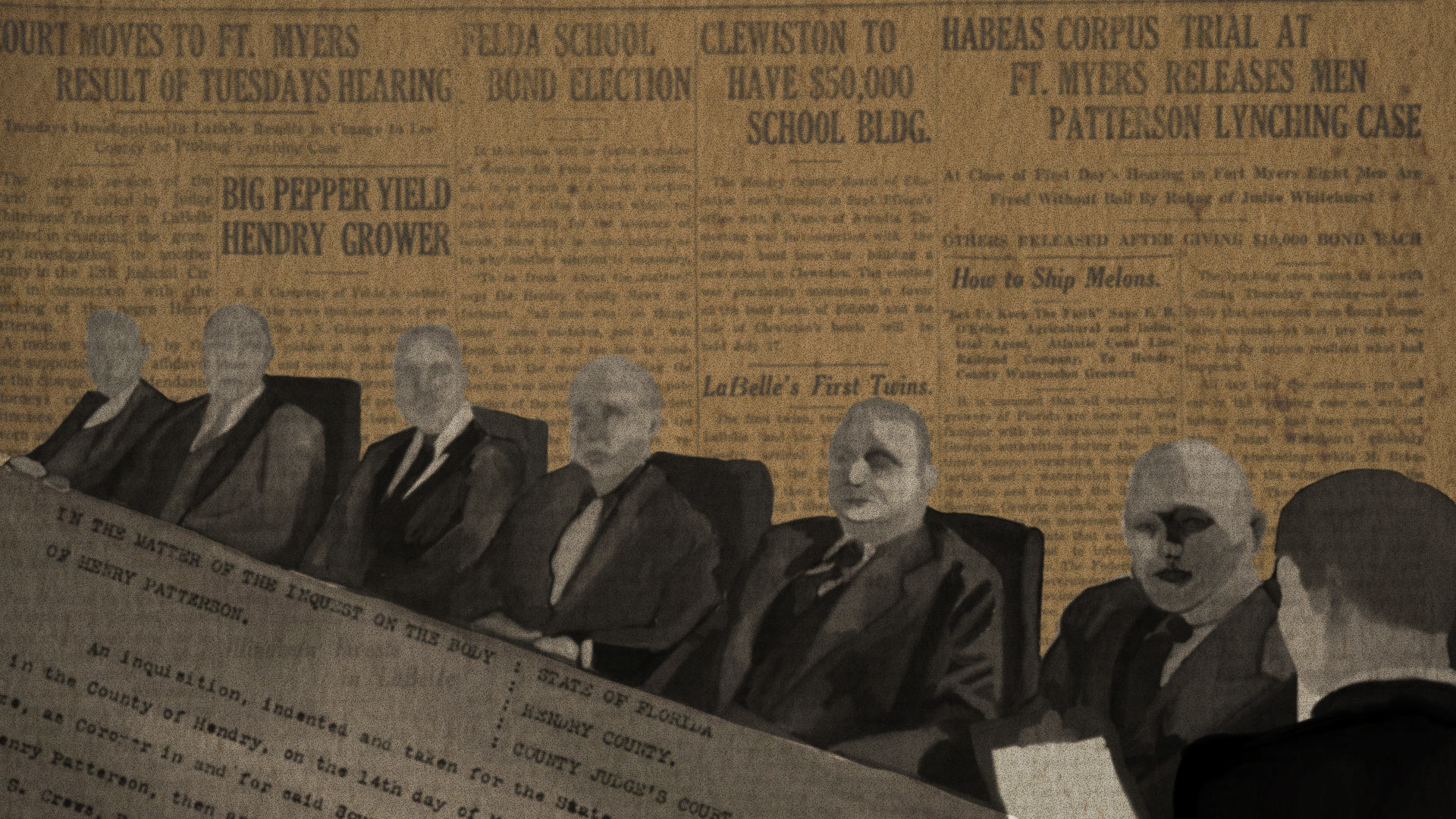

In response to the horrific events of May 11, 1926, county judge Wesley Richards convened a coroner’s inquest with the support of several locals. The coroner’s inquest consisted of Judge Richards and six other men, Finis Sylvester Crews, Steve Thomas, Edd Yeomans, M. C. Yeomans, William Blount, and Robert Hedges. The county prosecutor, Herbert A. Rider, questioned witnesses and gathered evidence at the inquest.

Tensions rose locally as the work of the inquest unfolded. Members of the mob threatened African American road workers and targeted the camps set up around town where they stayed while in town. Telegrams from local and state leaders flooded into Governor John W. Martin’s office. Patterson’s lynching was the second extralegal execution in Florida in just three days, the fourth in the last six weeks. Recognizing the negative economic impacts that lynchings had, Herman Dann, the president of Florida’s Chamber of Commerce, released a statement requesting the governor to investigate the lynching. Wesley Richards, Herbert Rider, and LaBelle Mayor Robert H. Magill released similar statements. Initially, Sheriff McLaughlin assured the governor that he could maintain order in town, but a few days later asked permission to deputize several locals to help him maintain order. By May 13, 1926, Governor Martin took matters into his own hands by sending Company F, 116th Field Artillery unit of the National Guard to assemble in LaBelle to maintain order and ensure the coroner’s inquest would be conducted without threats from locals.

"Coroner's Inquest" created by Joel Ralls, Rebeca Parra, and Joshua Oglesby

The coroner’s inquest unfolded behind closed doors for several days. Rider and Richards issued over 100 subpoenas for witnesses and, with the assistance of the National Guard and local sheriff, provided enough security that many those witnesses felt comfortable testifying and naming names of people involved. A few days into the inquest, local authorities made the first of a series of arrests. When it was all said and done, authorities arrested Driz Curry, Van Curry, Lemuel Howard, Ham Smith, Stanley Altman, James Cross, Lubbard Coleman, Harney Aultman, Herbert Tillman, Duane Cox, Coy Mercer, Colan Godbolt, Norman Warriner, Hurd Reeves, Radford Edwards, Dick Curry, and John Frazier, Jr. Despite the seeming tranquility of the inquest that accompanied the presence of the National Guard, there was one serious outbreak of violence. On the evening of May 14th, a tent at the worker’s camp on the outskirts of town was doused with gasoline and set on fire. This event only exacerbated the Black workers’ fears and an exodus of workers out of LaBelle followed the next day. The inquest formally closed on May 18, one week after Patterson’s lynching. In addition to the arrests, the gathered evidence would eventually be presented to a grand jury to determine whether a criminal trial should proceed. The conclusion of the coroner’s inquest represented a real departure in terms of the response of officials in Florida after a lynching. Typically, causes of death in lynching cases were left ambiguous with claims such as, “died at the hands of persons unknown.” In this case, suspects were named. On Henry Patterson’s official death certificate, the cause of his death is listed as “Killed by a mob and hung after dead in city limits of Labelle” and a secondary cause listed as “Booze + Prejudice.”

As the coroner’s inquest unfolded, Henry Patterson was unceremoniously buried in an unmarked grave on May 12th in the “colored cemetery in Glades County.”

Following the arrests, the judicial process slowly unfolded. On May, 19th, Louis Overton Graveley, LaBelle’s only other lawyer beside Herbert Rider, was announced as the defense attorney for the arrested men. The next day, Graveley petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus. The case came up in the 12th Circuit Court of Judge George William Whitehurst. Whitehurst issued the writ of habeaus corpus and held a hearing on May 31st. S. Watt Lawler, the State’s Attorney, made a motion for a change of venue for the trial, arguing that many locals did not believe lynching to be a crime and, more importantly, that a large number of locals were related by blood or marriage to the accused. Judge Whitehurst granted the change of venue.

The next step in the processes concerned the original habeas corpus hearing, which was convened in Lee County, Florida (the county just west of Hendry). At this hearing, the state called six witnesses first. The most dramatic and compelling testimony came from John Palmer (J.P.) Crews, a nine-year-old boy from LaBelle. Crews had been in a truck that was following the lynching party on the night of the incident and claimed to see the arrested men take leading roles in Patterson’s killing. The defense countered with several witnesses, including Dr. John Seebold who testified that he examined Patterson’s body and determined he had been shot between 50 and 100 times. In his estimation, it was impossible to determine who actually killed him. As the hearing unfolded, Judge Whitehurst unexpectedly called the attorneys to his bench and announced that he was prepared to issue his ruling. He determined that nine of the men would be held on bonds of $10,000 each and faced the charge of murder in the first degree, while the other eight would be released. By the following day, family and friends of the 9 men raised enough money to bond them out of jail.

Following this hearing, the attorneys, witnesses, and the accused prepared for the grand jury trial, which was scheduled for the fall session of the grand jury in Lee County on November 2, 1926. In the intervening months, the Florida real estate economy crashed and a massive hurricane shifted attention and momentum away from the prosecution of Patterson’s lynchers. Nonetheless, Rider sought assistance from organizations, most notably the NAACP, to assist in his preparation for the grand jury trial. The prosecution’s effort was made increasingly difficult by local circumstances, including, at least according to Rider, a majority of locals who did not wish to see the men accused of the lynching prosecuted and many of the state’s witnesses fled the area. Further complicating matters, Watt Lawler, the State Attorney, resigned from the case in September because he needed to devote time to his private practice and impending appointment to the state legislature. In his place, the governor appointed Guy Strayhorn, who would lead the prosecution at the grand jury trial.

The fall session of the 12th Circuit Court opened on November 2, but the grand jury would not hear the LaBelle lynching case until November 29th. State’s Attorney Strayhorn called twenty-one witnesses on the first day of the trial, including Hendry County Sheriff McLaughlin, J.E. Marshall, R.N. Miller, William Stallings, Solon B. Crews, Mrs. Crews, Frank Magill, Mrs. R.S. Taylor, Mary Lou Wall, Raleigh Dyess. J.R. Doty, Mary Hayes Davis, Finis Crews, J.P. Crews, Mrs. Nell Haynes Bush, Mrs. E.L. Rogers, John Williams, A.L. Hendrickson, C.J. Kirk, E.F. Fulghum, and H.O. Hansen. Observers noted that most of the witnesses were only in the grand jury room for a few minutes. Strayhorn called another eight witnesses the following day, including Dr. Seebold, John Redding, Doley “Hattie” Crawford, George Howard, E.M. Cornette, J.C. Jackman, M.J. Bush, and W.D. Blount. The final day of the hearing brought just one surprise witness into the grand jury chamber: Herbert Rider. Unlike the other witnesses, Rider testified for several hours. Noticeably absent from the list of grand jury witnesses was the young boy, J.P. Crews, whose testimony proved so decisive during the habeas corpus hearing back in June.

On Friday, December 3rd, the grand jury’s decision was to be handed down. Before issuing their decision, the grand jurors called in two witnesses, F. Watts Hall, whose home faced the park and jail where Patterson was taken from, Radford Edwards, the former town marshal, and Herbert Rider. During those deliberations, Guy Strayhorn and Wesley Richards engaged in a very public fight in the hallway of the courthouse. Richards was frustrated that Strayhorn did not call him to testify and that Strayhorn did not present the coroner’s inquest transcript to the grand jury as evidence.

"Lawyers Dispute" created by Joel Ralls, Rebeca Parra, and Joshua Oglesby

Although there appeared to be some consideration among the grand jurors for indicting some of the accused men for manslaughter instead of murder, those considerations did not go very far. On Saturday, December 5, 1926, the jurors did not return any indictments against the accused. Nonetheless, the grand jury railed against Sheriff McLaughlin for his dereliction of duty in protecting Henry Patterson and stymieing the mob. The grand jurors recommended the sheriff should be removed from office.

Thus, the lynching of Henry Patterson ended similarly to the over 3,000 other African Americans lynched in the United States: no punishment for the lynchers. Yet, the fact that the case made it to the grand jury stage was in many ways rare in the Jim Crow era, not only in Florida, but in the United States. Moreover, the public condemnations of the lynching, involvement of the governor and National Guard, and the sustained effort of officials like Rider and Richards, indicated that the era of complete, unmitigated acceptance of lynching was coming to an end in the state.